A Glimpse into the Void

Peering from the hotel window, off to the left of Mt. Illamani, La Cumbre and our morning adventure lay. Lipika and I nurtured a healthy dose of nervous anticipation. Given the hype of descending over 11,800 feet, from the Bolivian Andes to the jungle floor below and having watched the Discovery Channel documentary, aptly named "The Death Road", to bike on the world's most dangerous road seemed tangible. After all, there weren't any reported biking deaths in the documentary, which just detailed illustrations of the over 200 annual passenger vehicle fatalities, more than any other stretch of road on earth.

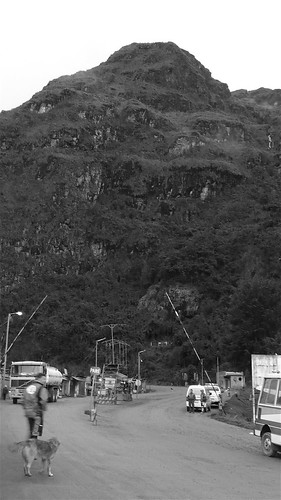

Our starting point was the saddle between two peaks, known as La Cumbre, about fifteen miles outside of La Paz. For our advertised adrenaline adventure we simply chose the oldest and best bike tour company, Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking, the one featured in the Discovery Channel documentary. There would be three groups of fifteen riders, each with guide and support vehicle. A fellow American and recent acquaintance, Ken, would be riding in the group in front, followed by two others.

The high altitude sun was piercing, as usual, but armed with sunscreen, a healthy dose of caution, nerves, and a smile it was time to get outfitted and tackle the challenge.

The entire crew was literally covered with protective gear, from the obvious helmets, goggles, and safety vests, to layers of outer wear and the company's flaming buff.

The guide was a Brit, with a knack for the dramatic. Everything was a verse of "do this, or do it exactly this way, else you will die." Thus far, the Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking company has guided over 30,000 tourists down the World's Most Dangerous Road, known on as the Yungas Road to the locals, without major incident.

Protective statues of Jesus dot the landscape of South America and this was one place where every road occupant, on bike or in vehicles, could use some shielding. Our crew even took the extra step of pouring grain alcohol on each tire and then a drop on the ground as a sacrificial offering to Patcha Mama for protection.

The first 12 miles of the the road are beautifully paved, with the only real danger being the unpredictable Bolivian drivers (who often drive drunk or high on stimulants) and handling the curves at over 30 miles per hour.

The really good news about Gravity, as an expedition company, is that they are careful and prepared, almost to an extreme. About every three miles, each group of 15 riders and their guide would stop for a briefing, where the next three miles of travel were mapped out in careful detail. (Our guide was picturesque against a clearing morning fog.)

We got to experience an optional three mile uphill slog, at altitude, prior to entering the "actual" death road or "World's most dangerous road" section. A slight right hand turn off of the pavement yielded a gravel road entrance. The guides conducted one final equipment check, for each bike and then challenged with "Want to know how to die at ten miles an hour?" That was a rhetorical question, because he was going to show us no matter what the response. All he did was take a random bike, accelerate to ten miles an hour and then lock up the breaks and ask, "How far did I just skid?" Six feet... Then he responded, "You will only have a foot and a half room to operate in for the next 27 miles. Do not ever lock up your breaks!"

Now, intimidated into submission, the group headed for the real test of endurance and psychological battle. The smallest cliff , for half a days ride would be over 100 ft. This one was significantly higher than that. (Note the bus negotiating the turn, in proportion to the cliff.)

To make things even more real our guide gave the group a brief review of the bicyclist toll over the last couple of weeks. Two weeks prior, a French woman fell off the edge and died five hours later. Last week, a rider lost his foot in a tangle with other bikers and a truck. Now we were stopped just before a hairpin turn because the guide's radio was alive with news of a woman, from Gravity's first group being injured from a fall ahead. (The first group's chase vehicles mark the spot off in the distance.)

As time slogged by, the mood changed from talk of minor injury to murmurs of something more fatal. Thirty riders waited a quarter mile away in radio silence as all the Gravity guides worked vigorously further down the road.

Over two hours passed and there was no sign of the woman who had gone over the edge. Incidental tourist doctors stood near the edge, hapless, and helpless to assist.

Then, we were all shuttled back up hill to a minor village near the road's source. The first group, from the stopping point further down the road, headed out first, with tear filled eyes. (Heading up the hill I dared to look back and down to an orange-clad body, some 200 ft or more down the rock strewn cliffs. Survival would be an impossibility.) Now, all three Gravity groups were huddled in one location. Every woman was accounted for, and then it struck. "Where's Ken?" I muttered to my self and then audibly, while pushing through the crowd. Finally, I approached the first group of riders, who had isolated themselves from the remaining riders. "It was Ken, wasn't it?" finally phonated. The response was a question, "Did you know him?" (Past tense was not the linguistic form I wanted to hear.) "Yes..." Nothing further was needed. It hadn't been a woman who had fallen, but Ken.

There can only be praise for Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking and their handling of this situation. Every aspect was completely professional. They were able to descend, via a winch system attached to each chase vehicle, get Ken on a backboard with CV collar and perform CPR for an hour and a half, prior to acquiescing his death. The guides were heart broken. Lightning had struck the most prepared and professional outfit and there was absolutely nothing that they could have done better. The Bolivian bureaucratic snags were bafflingly frustrating, as we had to wait for over an hour at a checkpoint, because the guards weren't sure of what to do with an ambulance carrying a foreigner's body.

As night fell, the mountains filled with fog and clouds, only adding to the dread and sense of gloom in the air. We were each stunned and crushed in midst of our own individual coping process. Lipika and I had a pretty quiet night, in denial, overrun by disbelief and eager for a change of physical/emotional scenery. The morning would bring a sprint up a 21,500 ft peak and we were hoping this titan struggle would help distract from the day's trauma.

No comments:

Post a Comment